I was visiting Seattle one spring, to escape the inevitable mud and snow of Bozeman and remember what green things looked like, when I walked into a small shop that sold Japanese saws. There was nothing on display, just boxes stacked in the back of the room and a counter with an older Japanese gentleman standing behind it. I had heard he had a particular type of Japanese saw that I was looking for and inquired about it.

“Yes, I’ve got one”, raising an eyebrow, “but it is not the best, you want to see the best.”

“Sure, I’ll look at it, but show me the one I asked for too.”

He reaches under the counter and pulls out an menagerie of blades, handles and some wood to demonstrate on.

He examined me as he handed me the saw I had asked him about, “you know how to use it properly?”

I took the saw and the piece of wood and started to cut.

“No, like this” and he took another saw to demonstrate a better stroke along with an explanation of the intricacies of the method. He was very accomplished.

It was a rainy, I didn’t have anything pressing, so I spent the next 45 minutes looking at and discussing the different saws he had; uninterrupted since no other customers had come in. I ended up buying a couple of the saws he that had demonstrated were the best and was getting ready to go.

“You use chisels?” he probed

“Yes.”

“Are they sharp?”

“Sharp enough, do you sell chisels too?”

“No, … You know how to sharpen them?”

“I do OK.”

“Draw what you think is sharp”, as he slid a piece of paper and a pen across the counter.

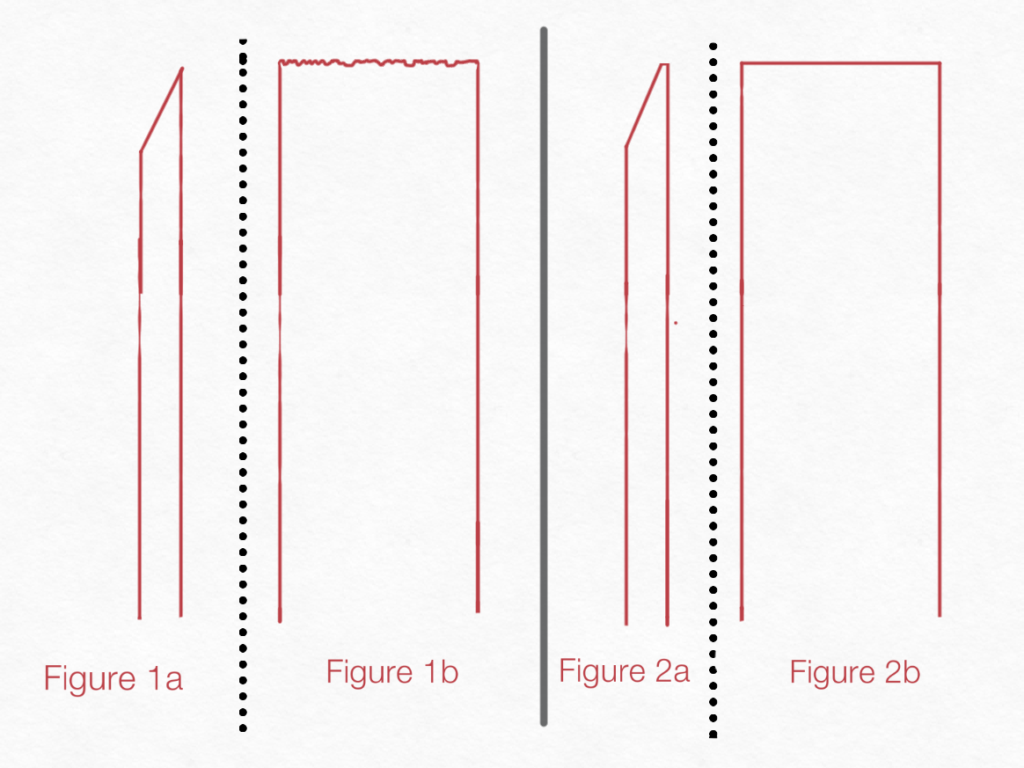

I made marks similar the the drawing in Figure 1a.

“That’s not sharp”, he then drew the a drawing like Figure 2a. “That is sharp”, while looking at me crossing his arms across his chest.

I took the bait. “what I drew is sharper than that.”

“Really?”, then he proceeded to lay out his case. It was a good case too.

He started by pointing out that when sharpening a blade to a fine edge, as in Figure 1a, there comes a point when the metal is so thin it has no structural support. In other words at the finest point where 2 planes of a piece of metal converge it is at places only 1 grain of metal thick and it is not consistent since even when using a very fine grit abrasive the grit of the abrasive is larger than the metal grains. The product of this process, if looked at under extreme magnification would look like the drawing in Figure 1b, and the edge so thin it would be fragile. While it would cut, or actually saw, and appear sharp it would dull quickly as some of the edge brakes off and other portions bend over. If fact when we use a sharpening steel to sharpen a blade, we actually aren’t sharpening it, but realigning the metal at the edge. With this process it doesn’t take very long before the blade is dull beyond the point of recovery.

In reality what we want to produce when sharpening a blade is not 2 planes converging, but 2 planes coming very close to converging then being joined by a 3rd plane that is the minimum thickness to keep the 2 planes from converging while remaining to maintain the stability of the metal’s lattice structure. This is best illustrated by the drawing in Figure 2a and the benefits and stability are illustrated by the drawing in Figure 2b. When you are able to achieve this configuration on a blade, it will cut smooth and remain sharp.

Great theory, but how do you get there? Well, he showed me and I’ll describe it as best I can, using a single bevel plane blade as an example. This process works on bi-bevel blades such as knives too, but requires some adjustments in technique.

Start by polishing the back side of the plane blade first to insure that it is flat. This is done by laying it back side down on a stone and working it until it has an even patina of abrasion from edge to edge. Next you will work the bevel, to do this you will need a guide to maintain a perfect angle while sharpening, I don’t believe anyone is able to hold it freehand precisely enough to meet the goal of creating a precision edge. Repeat this process, backside then front, until you are at the finest grit stone you will be sharpening with. While working with the last grit on the bevel polish it until you raise a burr all along the back side of the blade, then take the blade while holding it with the point resting on the stone and drag it smoothly about 1 inch, you just made your 3rd plane. Next, polish the bevel on the stone counting the strokes, checking for the burr to be raised again after each stroke. Once you get a burr again, hold the blade with the point on the stone and duplicate the drag you did previously. Now polish the blade one more time counting the strokes, but with 2 to 4 less strokes and you have a sharp blade that will maintain its edge.

A few details to be aware of:

- Insure your stones are flat. If you are using water stones they will develop a shape with use that you will need to addressed by flattening them.

- Use a 3 point guide so the blade will define its own cant.

Lastly, its been about 20 years since I had this valuable encounter and over the years I lost the contact information of the man that educated me on sharpening. I’ve tried to find this gentleman again unsuccessfully, but while writing this I searched one more time and I found him on the internet. The shop’s name is Tashiro Hardware, LLC, of Seattle, Washington and the proprietors name is Frank Tashiro. On his website tashirohardware.com he notes that he will be 93 in January of 2015 and It appears he is shutting up shop, but hopes to publish a manual on sharpening prior to shutting down his website. As of this writing he hadn’t published the manual yet, but I hope he does. Based on the education I got in his shop in a couple of hours, having his knowledge preserved in a manual will greatly benefit anyone who is interested in maintaining a sharp blade.